Gould Street Power Station

Updated June 28, 2023 | By Matthew Christopher

Photographing the Gould Street Generating Station in March of 2020 seems like a lifetime ago. It was the last place I visited before Covid sideswiped my life and career – and everyone else’s – and thus one of my last days of comparative normalcy in the Before Times, though of course I didn’t know it then. My visit was also during the last days of the power plant’s existence, as it had been purchased by Greenspring Realty Partners Inc. from Exelon for $3.25 million only a few months earlier in December, 2019 and demolition of the original 1905 section of the plant would begin in October, 2020.

I had passed the power plant many times, gazing wistfully at it from Interstate 95 during various trips through Baltimore’s Port Covington district. A friend had kindly arranged access through the developers, and as usual I was both excited and a bit anxious that something would go sideways before I got to photograph the interior. Thankfully, it did not: we met onsite with one of the developers, who was friendly and upbeat about plans for the property, the doors were opened, and we were left on our own for several hours. We started in the “modern” addition built in 1927 and still used periodically until 2019, and were struck by how clean and untouched the building felt. Later in the day we moved on to the original power houses built in 1905, and the difference was stark: while they were thankfully devoid of graffiti and vandalism, it was clear they had been out of operation for decades. It was the best kind of site visit – free of stress, plenty of time to work, and minimal interference.

The turbine hall in the abandoned Gould Street Power Station

The site of Gould Street Power Plant has a fairly rich history, as it is roughly located on the former site of Fort Babcock and prior to the start of demolition had a plaque and cannon on the property commemorating the fort’s significance in the War of 1812. Fort Babcock is described as “an earthen half-elliptical shore battery with six cannons” by The South Baltimore Peninsula Post that, in conjunction with the nearby Fort McHenry, Fort Look-Out, and Fort Covington, was instrumental in repelling the British naval assault in the 1814 Battle of Baltimore. Though the victory was immortalized in Francis Scott Key’s lyrics for the Star-Spangled Banner, Fort Covington and Babcock were mostly forgotten and in ruins by the mid-1850s.

At some point in the late 1800s the parcel of land that the Gould Street Generating Station would occupy came under the ownership of the Baltimore Brick Company, possibly in its 1899 acquisition of several competing brick companies. They in turn sold the 6.4 acre waterfront property to the Maryland Telephone and Telegraph Company for $45,000 and construction of Gould Street Generating Station, then known as the Gould Street Power House, began in 1904.

A welcoming doorway into the furnace section of the 1927 Gould Street Power House

The construction of the power plant was itself an act of war of sorts, though not between nations but rather companies. Baltimore was the first American city to begin replacing their system of whale oil lamps with gas street lamps in 1817 (although technically Newport, Rhode Island beat them by a few months to the installation of the first gas-powered street light) and the Gas-light Company of Baltimore, founded in 1816, was the first gas utility in the United States. The Gas-light Company had the monopoly as the sole provider of the city’s gas supply until after the Civil War, when competitors divided the city and costly price wars ensued. The 1880 merger between these companies formed the Consolidated Gas Company of Baltimore City, and while electric power was still considered experimental, it would soon become apparent that Edison’s incandescent light bulb was the future of lighting.

The first electric light franchise in Baltimore was granted to the Brush Electric Light Company in 1881, but their main power house was destroyed by a massive fire in 1893, an event which I’ve been able to find frustratingly little information about despite being briefly referenced as a major event in several newspaper articles. As with the city’s gas supply, a constellation of confusingly-named competing electricity providers appeared and vanished in mergers, but all were consolidated into the United Electric Light and Power Company in 1899. This company would then merge with the Consolidated Gas Company in 1906 to form the Consolidated Gas Electric Light and Power Company of Baltimore.

Another key event that would lead to the construction of the Gould Street Power House was the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904, which destroyed over 1,500 buildings and severely damaged approximately 1,000 more, causing over $150 million of destruction, which would be more than $5 billion today. During the fire, Consolidated employees raced to keep gas mains from exploding. There was much rebuilding to do in the aftermath, and a lot of money to potentially be made doing so. This was the moment that the Maryland Telephone and Telegraph Company decided to throw their hat in the ring.

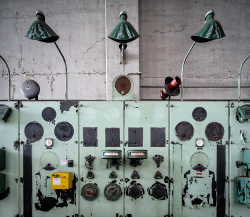

A beautiful intact control room in the older section of the Gould Street Power House

As with many industries including the power companies and railroads, the competition to provide telephone services to an ever-expanding base of customers had been fierce and the late 1800s and early 1900s were marked with a frankly bewildering series of new companies and subsequent consolidations and mergers that are more difficult to untangle than a long-forgotten jumble of Christmas tree lights. The Maryland Telephone and Telegraph Company had emerged on the top of the heap and boasted 9,000 Baltimore subscribers in 1904. Their decision to branch out into light and power was more of a natural progression than it might seem – they had already installed phone lines across the city that could also carry electrical wires. With the backing of Maryland Telephone and Telegraph Company officers, the Baltimore Electric Power Company was incorporated, and the Gould Street Power House was to be their flagship plant.

Funding was provided by George R. Webb, who had started as a clerk at the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Company, spearheaded a series of consolidations, and wound up as president of the United Railways and Electric Company. Webb’s name is forgotten today despite some pretty incredible accomplishments. Though it’s not particularly relevant to Gould Street, Webb was also an inventor – he would develop arguably the first public address system, called the Magnaphone, which was installed on riverboats, ships in the US Navy, and at Grand Central Station in New York City. He also created a “Music By Phone” service in 1908 that functioned as an early sort of pay-per-listen service allowing subscribers to play news and popular phonographs via dedicated speakers, roughly two decades before most US households had radios. Webb also invented a system to synchronize sound with film and was showing talking motion pictures in 1912, a full 15 years before the first talkie, The Jazz Singer, debuted in 1927. Had World War I not occurred, which stifled Webb’s efforts to gain worldwide implementation of his inventions, and had Webb not died shortly thereafter from a heart attack in 1919, it’s possible that he might be known as one of the great American inventors rather than an obscure footnote. This is in addition to his work laying the foundation for telephone service to cities like Baltimore and Pittsburgh. But, I digress.

An exterior view of the older section of Gould Street, opened in 1905

The Gould Street Power House was estimated to cost $2 million to build, and would be “thoroughly modern and fireproof”. It was steel-concrete construction with curtain walls of brick laid in cement, and utilized Westinghouse steam turbines and boilers from the Sterling Boiler Company of Chicago. The contractor was John Waters, who sadly is unrelated to the famed Baltimore film director. The power station was located so that it could receive coal by rail or water. When Gould Street opened with a production capacity of approximately 8,000 horsepower in 1905, it must have been a somewhat terrifying development for Consolidated, who started construction of their own flagship Westport Generating Station (also on my site here)that same year and began operations there in 1906. A short but fierce price war took place which saw the Baltimore Electric Power Company losing money from selling electrical service for less than the cost to produce it in hopes of securing their position. This led to a failure to pay their bonds, and they were consolidated by Consolidated in 1907 or 1908.

As the city’s electrical demand could be carried solely by Westport, Gould Street was used as a backup during periods of peak demand. B&O Railroad sought unsuccessfully to lease the plant in 1909 and it was noted that it was in use in 1913 despite most city residents thinking it had been mothballed. That same year a night watchman named Joseph Wallace who had interrupted an attempted robbery of a safe at the plant at some earlier point was found “riddled with bullets” in a swampy area adjoining the Gould Street property, presumably in retaliation for his testimony against the would-be robber. The most incredible part of this story was that Wallace had been shot 5 times – three times in the abdomen and twice in the back of the head – and employees even reported seeing the assailant running away, yet police were initially convinced that Wallace had somehow committed suicide.

Gould Street’s function over the next decade or so is ambiguous. One source cited in the brief Wikipedia entry states that that the generators and turbines were shipped to a silver mine in Mexico, but I’ve been unable to find any direct newspaper sources confirming this; during my visit the equipment seemed intact and the building bore no traces of having been ripped open to remove anything, although I could certainly be mistaken. In 1923 there was a scuffle over the property when Western Maryland Railway Company attempted to get right of way across the property and the Port Commission considered condemning the Gould Street site to resolve the dispute, which would imply that the plant had been out of use for some time. Consolidated had been experiencing enormous growth as more homes were electrified and industrial use increased, and argued that they needed the site for a new power plant. This included a 25-foot strip of land on Western Maryland Railway Company’s property that in 1926 Consolidated argued should be condemned. As there’s no record I can find of whether either company’s attempts were successful, it’s not clear whether Consolidated was trying to recover land they lost or just trying to smack the railway back for trying to take their property via condemnation in the first place. Either way, it reeks of a certain vindictiveness that likely greatly pleased Consolidated executives when it was set in motion.

A gorgeously decayed area in the 1905 Gould Street buildings has clearly been out of use for many years.

Whatever the case may be, work on the new addition to Gould Street began in 1925 with the demolition of two 200-foot chimneys, each weighting 700 tons, and an iron coal elevator. The Baltimore Sun article about the demolition marvels at the precise use of dynamite to bring down the structures, which also hurled debris into a nearby crowd of spectators. Thankfully, none were injured. The new plant cost an estimated $4 million to build and had an output of 213,000 horsepower – more than all of Consolidated’s plants in 1910 combined. It opened in 1927, crowned with two brand-new smokestacks that would serve as a navigation marker for ship captains in the decades to come. The new turbines used pulverized coal and were considered engineering marvels.

Consolidated rebranded as Baltimore Gas & Electric, or BGE, in 1955, and to meet ever-increasing demand they built Maryland’s first nuclear power plant, a two-unit facility in Calvert Cliffs whose reactors went online in 1975 and 1977. As a result, two of the three units at Gould Street were decommissioned, but Unit 3 continued to operate sporadically for peak summer demand and energy shortages. In 1996 the smokestacks on Unit 1 and 2 were removed and scrapped, hoisted off in 35,000 pound sections by a 300-foot crane. Exelon acquired BGE’s parent company Constellation Energy Group in 2012 and continued periodic use of Unit 3 until June 1, 2019, when the entire plant was closed for good and sold six months later to Greenspring Realty Partners Inc.

Lost in the basement of the mammoth turbine hall at Gould Street

Currently the property is controlled by the Port Covington Development Team (later rebranded as Baltimore Peninsula), which, according to SouthBMore.com, consists of “lead investors Sagamore Ventures and Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group, and lead developer Weller Development Company.” Though there are no current indications what future plans for the Gould Street property are, Baltimore Peninsula’s projects in the immediate surroundings suggest a mixture of residential, retail, and office use. A short walk nearby will take you by the Sagamore Spirit Distillery, the Rye House (an apartment complex) and Rye Market (a food hall and shopping center), and the new Under Armour headquarters, which has an accompanying track and field facility. It’s clear that Baltimore Peninsula wants to make a hip new neighborhood where many of the city’s defunct waterfront industries used to be, and it’s a safe bet that the Gould Street Generating Station property will factor into that.

Anyone who knows me knows that I will always favor adaptive reuse of historic buildings, and I do think that the Gould Street Generating Station would have made a terrific centerpiece property had it been rehabilitated through an inspired project like the one that is nearing completion at Philadelphia’s former Delaware River Generating Station. The Gould Street buildings that were demolished were, in my opinion, easily the most handsome of the ones on the property, and I’m sad to see them go. Given my way, I would have preferred to see the old waterfront brought to life as part of the new.

Having said that, it’s hard to argue that the property Gould Street Generating Station sits on serves the community better as the site of a defunct, polluted relic of coal-fired power production than the mixture of homes and businesses that are popping up around it. One day the remnants of the industries from the late 19th and early 20th centuries that created our urban centers will be nothing but fading memories, and while I’ll always hope that more can be integrated into our contemporary lives, their legacy in terms of land use and environmental impact is likely best left behind.

There’s nothing quite like seeing the scale and might of a grand old power plant like Gould Street firsthand though, that much is for sure. There’s something awe-inspiring and humbling about being in a massive turbine hall that once cranked out enough energy to fuel an entire city, and seeing the long-forgotten guts of an engineering marvel that was once the pride of the town that built it. I’d go back to Gould Street Generating Station in a heartbeat if I could, just to walk through the maze of boilers and furnaces and pipes without the pressure of taking photos. I’d sit in the silence of the turbine hall and watch the way the light changed as it filtered through the grimy windows at different times of day, just appreciating the plant as it was after its utility ceased to define it. It’s in conditions like those that the billions of lost seconds throughout the course of a century seem so close that you feel like you might be able to pierce through the veil of the present and bathe in them, unshackled by time or place. There’s a kind of magic to it that I have never really felt able to condense into words, but it’s the defining factor that has driven the many years I’ve spent hunting down abandoned places. Maybe you could call it a sort of annihilation or obliteration, a loss of self. Maybe you could call it peace.

To view more photos of this site click on an image in the gallery below; use arrow keys to navigate.

👉 Join Abandoned America on Patreon for ad-free high quality photos & exclusive content

👉 Make a one-time donation to help keep the project going

👉 Listen to the new Abandoned America podcast

👉 Subscribe to our mailing list for news and updates