Northern Central Grain Elevator

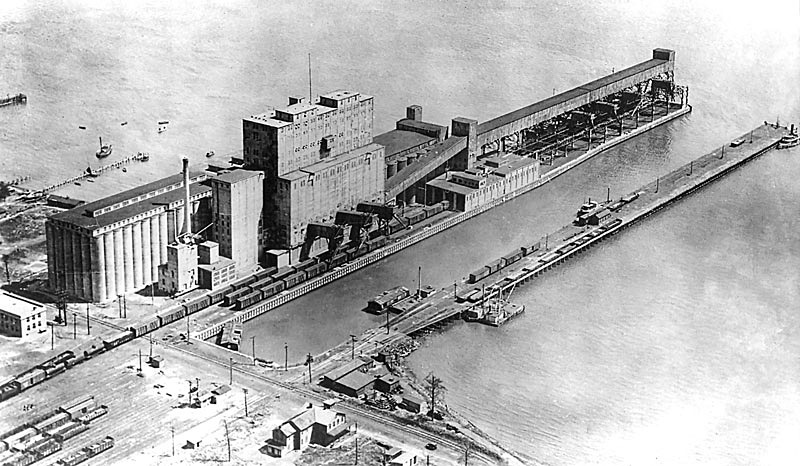

Baltimore's Northern Central Grain Elevator circa the 1920s. Image by Hughes Co.

Updated February 1, 2022 | By Matthew Christopher

If, like me, you have a limited knowledge of grain elevators, you could be forgiven for thinking they are somewhat boring. Storing grain seems like it would be relatively routine, but in actuality if done incorrectly it can have consequences that rival big budget disaster movies in terms of spectacle and loss.

Grain is flammable, but more importantly, grain dust in the air is incredibly flammable – combined with the oxygen in the air, any errant spark can cause an enormous ball of flame. Worse, the silos are enclosed spaces which magnify the blast. A short in the wiring, a light bulb, a mechanical failure, someone smoking, or even nothing more than static electricity can turn multistory silos into pipe bombs throwing concrete shrapnel into the surrounding area. Compulsive cleaning to prevent dust buildup and engineering that doesn’t give grain dust areas to settle are critical, but even then accidents can occur, particularly when the air is dry. Between 1976 and 2011 OSHA records show that 503 grain elevator explosions happened in the United States, an average of over one a month.

The Northern Central Railway’s grain elevators on the Canton waterfront of Baltimore were both literally and figuratively an enormous part of the area’s industry. An 1881 blockade at the grain elevators, which occurred because speculators wished to store their grain until prices rose and filled Northern Central’s silos to capacity, threatened to paralyze the entire country’s wheat market. Outside the silos, five thousand train cars stretched all the way to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania with nowhere to take their grain, except for the more expensive and thus less desirable silos at Locust Point.

Nine years later, Northern Central’s No.3 elevator was filled to capacity with 50,000 bushels of corn, or approximately 1,750,000 pounds, when it exploded on the night of January 13, 1890. $280,000 worth of corn and the $300,000 elevator (a combined total of nearly $17.8 million today) were destroyed. In addition, a British steamship in the harbor was obliterated by the blast, with three crew members killed and four badly burned. Sailors jumped in the water to escape the flames and some were not rescued until two hours later. Two more nearby vessels had their masts, rigging, and upper decks wrecked as well. It’s hard to picture just how large and powerful the explosion must have been to cause such damage.

Aerial view of Baltimore's Northern Central Grain Elevator; date and photographer unknown

The new Northern Central Elevator, completed in 1922 but with parts that dated back to 1905, surely had events like these in mind. Lauded for both its scope and its modernization of the process of importing, storing, and exporting grains, the Northern Central Elevator had a staggering capacity for five million bushels and was built almost entirely of concrete, so as to minimize areas in which dust could collect. It was the largest elevator on the East Coast, and boasted a number of extraordinary features including massive freight unloaders that could pick up railcars full of grains and tilt them about to empty out their cargo. The list of features was breathlessly described in the article “More Than Modern, The Northern Central Elevator at Baltimore: A Structure That Is Ahead of the Times” by Jay Williams, and included a facility-wide phone system that could automatically activate the emergency response systems.

Little that was noteworthy enough to make the news occurred in the years to come. Northern Central Railroad sold the silos to Central Soya in 1970, and President Carter’s 1980 grain embargo against the Soviet Union for their invasion of Afghanistan drastically reduced the grain export business. Central Soya became Mississippi River Grain Inc., which was then sold to ConAgra Inc. in 1994 when the Italian holding company that owned Mississippi Grain collapsed and was forced to liquidate its assets. By this time the grain shipment industry had been relocated from the East Coast to the Gulf of Mexico and the Mississippi River. ConAgra decided the Northern Central Elevator would remain closed after the sale, and so the building was left abandoned for over a quarter of a century.

Interior view of pipes in Baltimore's abandoned Northern Central Grain Elevator

In the years that followed, the Northern Central Elevator was featured prominently in the opening of the 2004 firefighter thriller Ladder 49, but beyond that garnered little notice. When I visited the Northern Central Elevator in 2019, demolition of the silos was already underway but most of the main building remained intact. Filthy water the color of stout beer poured through the building, forming disgusting, foamy pools on the floor and leaking down from stairwells and holes in the ceiling. Keeping my camera lens dry was a challenge, and I felt like I had been soaked in sewage after I left. It was not an entirely bad experience, however: for example, the pipes inside were like nothing I’d ever seen. They stretched from the floor to the ceiling at odd angles, resembling vast steel arteries. The view from the top of the building was satisfying, and the blackened, monolithic exterior seemed more like something from a half-remembered dream than a real building. Demolition of the site concluded in 2021, with no future plans for the property that I am aware of as of this writing.

Exterior view of Baltimore's abandoned Northern Central Grain Elevator during demolition

It's easy to write off abandoned places as failures, but given Northern Central Elevator’s scale and industry, the fact that it operated safely and did not explode at any point in its 72 years of operation is not to be underestimated. Historic grain elevators across the United States are vanishing rapidly, and while I wish there had been an adaptive reuse project like the residential complex at the former Baltimore and Ohio Locust Point Grain Terminal Elevator, finding a way to repurpose such a large, deteriorated, and purpose-built complex is not always feasible. Still, the Northern Central Elevator was one of the primary sources of grain for the entire country and revolutionized its entire industry. I may not have enjoyed being doused with cold, nasty water when I visited it, but I respect the building nevertheless.

Listen to the new Abandoned America podcast here!

Join us on Patreon for high quality photos, exclusive content, and book previews

Read the Abandoned America book series: Buy it on Amazon or get signed copies here

Subscribe to our mailing list for news and updates